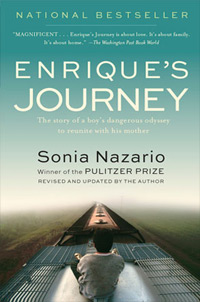

This week, TheLatinoAuthor.com is featuring author Sonia Nazario. Not only did Sonia spend over 20 years reporting on social issues, but in 1998 she was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for a series on children of drug addicted parents. She has since continued her passion to write and bring serious issues to the forefront. Read the interview and see what compelled Ms. Nazario to become a successful journalist and an award winning author. Her story is amazing!

Tell us a little bit about yourself; where you grew up, where you currently reside, family upbringing, or anything that you would like our readers to know about you?

I grew up in Kansas and in Argentina. My parents are both from Argentina, and I am the only one in my immediate family born in the U.S. I decided to become a journalist after what I experienced living through part of the so-called dirty war in Argentina, where the military took power and “disappeared” up to 30,000 people. Two journalists near my home in Buenos Aires were killed for trying to tell the truth about what was happening. Seeing the blood on the ground where they had died convinced me (I was 14) that I wanted to be a journalist.

I understood at an early age that journalists play a critical role in holding people in power accountable and in bringing critical issues to light. I have always focused on writing about social issues, social justice issues, and folks I feel don’t get enough attention: women, children, the poor, and Latinos. At first I wanted to write about Latin America. When I was 24, I was the back up correspondent for the Wall Street Journal for Latin America and soon realized there were plenty of burning social issues that I wanted to write about here in the United States.

In college, you majored in History and Journalism. What prompted you to focus your academic studies in this direction?

My choice in college was to either study Journalism and learn the craft of preparing a news story, or focus on a broad liberal arts education. I wanted to write about social issues and social justice issues, so I chose History over Journalism hoping it would give me a foundation of knowledge that would help me better understand and put into context complex issues I planned to cover. I knew I could learn the craft of journalism later, once I started working at a newspaper.

From the time I became a full-time reporter at the Wall Street Journal at the age of 21, I made an art of finding the best editor in the newsroom—someone who could help me hone my journalism skills. I had some great teachers along the way who helped me get better and better. I believe a big part of success in anything is persistence, sweat, determination—ganas—and another part is shamelessly glomming on to mentors who can help you get better.

On being a writer or a journalist (have commonalities yet different) which of these do you prefer? Which of these two professions do you find more challenging and why?

I don’t see them as inherently different. A good narrative journalist writes stories with the same elements in mind as a good book writer. You look for stories that move you emotionally [I know I have a good story when someone tells me about it and the hair goes up on my forearm!]. Stories that have a beginning, middle and end, with a great narrative arc. Stories that have compelling characters that grow or change over time. Stories with conflict, and a question that makes you want to read on to the end.

Both journalism and book writing allow me to pick a topic I know nothing about, go out into that world, and ask a lot of questions. It’s wonderful to delve into new worlds, meet interesting people, and feel that I can truly get my arms around an issue. But journalism as it is increasingly practiced now, with newspapers facing a financial crisis, can be very limiting, both in terms of the time and space given to explore stories and issues. So now I prefer telling stories in books where there is the freedom and space to really tell a story from beginning to end and do it justice.

How different was it to write as a Journalist versus writing an actual full length book? What type of preparations did you make, if any?

In some ways it is very similar, and in some ways very different. With both I look for stories that move me on an emotional level, because if they move me they will likely move my readers. And I look for stories that take you inside worlds you might never otherwise see [the top of a freight train], and shed light on complex issues [immigration].

When I expanded a newspaper series into the book Enrique’s Journey, I went back and re-traced the journey again–another three months of travel. This second journey allowed me to give a deeper sense of other critical characters besides Enrique, like his mother Lourdes. It allowed me to spend time describing the work of amazing people along the tracks in Mexico. People like Olga Sánchez Martínez, who has a shelter for persons mutilated by trains, or Padre Leo, a priest who helps migrants in northern Mexico. By widening the lens of the story a bit, it nearly quadrupled in length and added many compelling characters and scenes and turning points to improve the story.

Do you feel that your career as a Journalist opened up doors for being a successful author? Would you recommend this to up-and-coming writers?

I think being a successful book author is difficult whether you come at it as a journalist or as a book author. It’s a crowded field. Contrary to the perception many have, 99% of authors have to have a day job to pay the bills. Writing books is often secondary to that primary job, whether it is journalism or teaching.

Journalists perhaps do have three key advantages: we are used to having our work torn apart by editors. We see this as something that [given the right editor] results in a better story, so we are more open to this and perhaps more thick-skinned about it. Second, we perhaps understand the value of publicity better than others, and how to obtain publicity through newspapers and TV to try and better bring our book to audiences’ attention. We’ve learned through our work not to be shy in asking people for help for what you need. Finally, many authors are asked to speak about their books. Unlike some fiction writers, journalists are typically extroverts, so speaking may be an easier fit.

Although you are currently published through Random House (one of the major power publishing houses of today), many authors are choosing to self publish. What are your thoughts on these two types of publishing mediums?

There are roughly half a million books published each year. How do you get readers to know about your book and read it? Big name authors have a following of fans who buy every book they write. For everyone else, it is hard to get noticed. If you self publish, the onus is completely on you to make people aware of your book and to market it.

The publishing houses still serve a very useful purpose. They helped me push my book into bookstores like Barnes & Noble. They sent me on a publicity tour and helped me get on the Today Show and CNN and NPR. Their academic department helped flag the book to potential colleges and universities to consider it as a common or freshman read. When I sell a paperback, I get $1 a book. I might get much more self-publishing per book, but there are definite advantages to using the assets only big publishing houses like Random House can bring to the table.

You wrote the book Enrique’s Journey. Why this topic and why this book?

I learned of this topic through a woman, Carmen, who would come and clean my house twice a month. She was trying to figure out what was wrong with me. I had been married seven years, Latina, with no children. I seemed like a nice person, but to her all of this added up to that there must be some monster lurking inside. So one morning in my kitchen she asked, “Mrs. Sonia, cuando va a tener un baby?” I didn’t want to answer, so I asked if she wanted to have children—beyond the one son I knew about. She started crying and told me she had left four kids behind in Guatemala, and hadn’t seen them in 12 years. She was a single mother, her husband had left her for another woman, and her children cried with hunger at night. She had nothing to give them. In my kitchen, she showed me how she would gently coax them to roll over in bed and say, “Sleep face down so your stomach doesn’t growl so much.”

When she left her four children with their grandmother in Guatemala and came north to work in Los Angeles, CA her youngest was one year old. Her son came up on his own from Guatemala desperate to be with his mother. He told me about a small army of children coming north each year, alone and unlawfully, in search of mothers who had left them behind. I thought: this is such a moving story. It’s about universal themes anyone can understand—the love between a child and his mother. But I also saw it as a way to talk about immigration in a different way—a way anyone could understand—the bond between a mother and child. And to try to take people inside the world of one migrant family at a time when because of a huge influx of immigrants, there was growing hostility towards them.

I saw it as a way to show people what’s pushing migrants out of their countries and what are they willing to do to get here. As migrant destinations have extended beyond the six traditional states, telling this story could introduce Americans to their newest neighbors. It was also a way to show how the face of people migrating to this country had changed—during a period [1990-2010] when more migrants came to the U.S. than any other time in this nation’s history. More than half of undocumented immigrants were now women and children.

The issue of child migrants has become even more pressing since Enrique made his journey. In fiscal 2014, the federal government expects to catch and put into federal custody 74,000 children coming to the U.S. unlawfully and alone, ten times the number just three years before. Children are fleeing gang and narco-trafficking violence in central America, and many of them are coming to reunify with a parent, but they are also fleeing recruitment by gangs and certain harm. They are fleeing for their lives.

In your book, Enrique’s Journey, you write about a boy who was left behind in Honduras by his mother. He then struggles to get to the U.S. to find her. Out of all the millions of children that are caught in this vicious cycle, why did you chose to write about Enrique? What specifically drew you to him?

I was searching for someone who was typical of teenagers making the journey to the U.S. alone in search of parents in the U.S. The average age of a lone child coming to the U.S. [without either parent] and illegally is 15 years old. Three in four are boys. I wanted a 15 year old boy who was coming on top of freight trains and going in search of their mother. When a nun at a church in Nuevo Laredo put Enrique on the telephone with me, I liked him because he was honest, open, and had been through many difficult experiences these children face. He had almost been beaten to death on top of the trains by thugs. He was willing to tell his story. I worried he was a little too old as he had started his journey when he was 16 and was 17 when I met him. When I went to Nuevo Laredo to interview him in person, I discovered he used drugs and sniffed glue. So I kept searching for what I saw as a more ideal candidate—younger and more angelic. But every younger child I interviewed; 11, 12, and 13 year olds had all been robbed of the slip of paper they carried with their mother’s telephone. They hadn’t thought to memorize it. Enrique at least remembered a number he could call in Honduras to get his mom’s telephone in the U.S. He had the chance of continuing on his journey and finding her. I called my editor and he said, “The best characters in literature aren’t perfect angels. They are deeply flawed. Readers can’t identify with someone who is perfect.” He urged me to go with Enrique, and it turned out to be sage advice.

I understand you did a lot of extensively hands-on research to write Enrique’s Journey. What was the most difficult part you encountered during your research? What would you have done differently?

I wanted readers to feel they were sitting next to Enrique on top of that freight train as he made this modern-day odyssey. The only way to do that was to recreate scenes in gripping detail, and to do the journey myself. It involved re-tracing Enrique’s journey just as he had done it a few weeks before. I started at his grandmother’s house in Honduras, rode buses to southern Mexico, got up on a freight train in southern Mexico, and rode on top of seven freight trains to the place where Enrique got off. Then he hitchhiked on a truck, and I did the same thing from the exact spot. I was trying to tell the story through his eyes. It was effective but dangerous. I had many close calls, and when I returned to the U.S. after the 1,600 mile journey, I had a case of post traumatic stress.

Despite everything I went through [almost getting swiped off the moving freight train, having a gangster try to grab me on the train with the clear intention of doing me harm] the hardest part was having many migrants each day ask me for help, either money or food. Journalists are taught to be observers and not change the stories we are writing about because changing something and then writing about it is considered dishonest to readers. So unless a migrant I encountered was in imminent danger [in which case I did intervene], I told them I couldn’t help them. That was by far the hardest part of this journey.

Describe a typical day in the writing world of Sonia? How is your daily schedule balanced between writing and marketing? Which do you find more challenging and why?

I’m usually up early and read four or five newspapers over a couple of cups of coffee. I specialize in immersion reporting, where I put myself in the middle of the action and watch it unfold in order to put readers in the middle of critical scenes. If I am in reporting phase, I can spend 10 or 12 hours a day following someone I am writing about. If I am in writing mode, I try to carve out from 10 am to 5 pm to write. The best writing happens when I can block out everything else and enter that world or scene I want to convey. I get what seems like a daily deluge of emails. I try to leave answering most of them until the evening, or weekends.

What word of advice can you provide to upcoming writers on being successful in the writing world of today with the internet and digital age technology at hand?

I would advise them to develop a following of fans on the internet and to have a strong digital presence to engage actively with those fans. They are what carry you, and they love being kept up to date on the issues you address, your triumphs and defeats, and what to expect from you in the coming months or years. It’s great to have fans along for the ride. It makes it much more meaningful. Some emails I get from readers provide the most uplifting part of this job. I get emails every day from students who tell me they were raised racist and anti immigrant, and that my book and class discussions about the book have changed their perspective about these people. They can at least now see a different perspective, or range of perspectives.

At the end of the day, what do you want your readers to take away from your writing? What impacts do you hope your writing will have on your audience and/or society?

I always hope to educate people about the biggest issues of our time in a compelling, engaging way. I want to grab them by the throat and take them on a ride, take them inside a world they might not otherwise see, and educate them about that world. Ultimately, I hope that if people see something that’s wrong, that’s unjust, they will act in some way—big or small—to address that issue. It’s a lot for a writer to hope for, but I see readers doing this every day.

Many have taken to heart my message that the best solution to the immigration issue is to help create jobs in four countries that send 74% of unlawful immigrants to the U.S.; fewer women would then feel forced to leave their children. One reader in Indiana quit her job and went to Honduras to open a café and employ 10 people. A high school in California raised $9,000 selling cookies and used the money to provide a micro-loan to women in Guatemala so they could expand their coffee growing business and hire more workers so fewer women would have to leave for the north.

Your book is highly regarded in many circles and as a result you have many loyal fans and readers. What upcoming books or projects are on the near horizon?

I just completed a young adult version of Enrique’s Journey for middle school students and reluctant readers in high school, and a revised and updated version of the regular book, as well. Spanish versions of both of these versions will be out in 2014. I currently split my time between working on another book for Random House, speaking about Enrique’s Journey across the U.S. and internationally, and sitting on the boards of three nonprofits and helping them with their missions. It’s a lot, but all of it is incredibly fulfilling.

Contact: Sonia Nazario

[…] being a writer is hard work that sometimes seems like it will never pay off. Even notable author Sonia Nazaro says, “I think being a successful book author is difficult.” It’s true that it’s hard to make it […]