This week, TheLatinoAuthor.com is featuring author and educator Dr. Alvaro Huerta. Dr. Alvaro is a scholar with specialization in urban planning, ethnic studies (particularly Chicana/o studies), immigration, social networks and the informal economy. Being the son of poor Mexican immigrants, he went on to excel in education and now writing. Read the interview for some great insight into how he moved forward and became successful in his education and career.

Begin by telling us a little bit about yourself; where you grew up, where you currently reside, and what you would like our readers to know about you?

Currently, I am a Visiting Scholar at the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center and interdisciplinary scholar with research specializations in urban planning, ethnic studies (particularly Chicana/o studies), immigration, social networks and the informal economy. I have published in peer-reviewed journals, university presses (books), national newspapers, edited volumes and encyclopedias. Also, apart from my scholarly interests and publications, I have a long history of student engagement and civic participation in Los Angeles and beyond. In addition to earning a B.A. (history) and M.A. (urban planning) from UCLA, I hold a Ph.D. (city & regional planning) from UC Berkeley.

Overall, as a son of poor Mexican immigrants, I want your readers to know that you can become successful in this country without forgetting your roots (especially if you started at the bottom, like myself) and that with great privilege, comes great responsibility to impact the world for the better.

As I read some of your early history, I see that you grew up in poverty. How do you think this impacted your life – both from a positive and negative perspective?

Originally from rural Michoacán, Mexico, my parents abandoned their small rancho due to a bloody family feud and to pursue better opportunities for their growing family. They, along with my large extended family, relocated to an impoverished canyon in La Colonia Libertad in Tijuana. The slum conditions included make-shift homes, outhouses, contaminated water and dirt roads. While conceived in this slum, I was born in the U.S., where my mother commuted and worked as a domestic worker cleaning the homes of wealthy Americans for measly wages. However, I only spent a month in el norte before returning to Tijuana to be with my family. Too busy to support her impoverished family, my mother would regularly return to the U.S. for long periods, where my older sister cared for my siblings and me. In fact, I have few memories of my mother during my early childhood.

When I was four years-old, our family migrated to the U.S., permanently. We first lived in Hollywood with our extended family, which included countless uncles, aunts and cousins. Tired of the lack of privacy, my mother applied for public housing in East Los Angeles’ notorious Ramona Gardens housing project. Little did she (and, later, my father) know that applied to one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in the country plagued with poverty, gangs, violence, drugs, over-crowded schools and police abuse. This was definitely not an area to raise eight children, yet poverty limits your options.

Growing up in Tijuana and Ramona Gardens didn’t bother me at first, especially since I thought that everyone in the world lived under deplorable conditions with contaminated water, dirt roads, railroad tracks, freeways, factories and poor schools. These harsh conditions also included experiencing and witnessing violence from local bullies and the police. Not until junior high, when I participated in a school busing program to the suburbs with mostly white kids, did I realize that I was different—i.e., Mexican, poor and from the projects. That was the first time that I felt something was wrong, that not all kids have to worry about getting “jumped-in” into the local gang or being harassed by the police for the color or your skin, including an array of stigmas associated with so-called kids from the projects.

Not feeling that I belonged in the projects, as I got older, partly because I’ve never been “gang material” due to being a thin kid/teen, I enrolled in a summer residential program, Upward Bound at Occidental College—a federal program to promote higher education for historically disadvantaged kids. Apart from my natural gift for mathematics and support from key individuals (e.g., parents, couple teachers and counselor), this program facilitated for me to be accepted to UCLA as a freshman. Being accepted to UCLA represented a huge accomplishment for me, given that the vast majority of my childhood friends dropped out of high school, ended up in jail, became gang members, committed suicide and / or killed by the police.

Reflecting on this period of my life, while I am still angry that I had to experience and witness so much despair and darkness, I am also privileged that I survived it with few emotional or physical scares. I only wish I could say that for my childhood friends and siblings.

Today you are a successful professor teaching and lecturing in some of the highest academia circles and universities. What perspective do you bring to your audiences that your peers may not? What sets you apart from them?

Spending most of my youth in the mean streets of East Los Angeles, I am one of the “lucky ones,” not because I received advanced degrees from the best public universities in the world, but because I am alive today to study, write and advocate against the daily injustices committed against residents of America’s ghettoes, barrios and reservations. I find it morally appalling that we still have so much poverty and violence inflicted upon human beings, particularly racial minorities, in the most advanced country in the world.

That said, unlike most of my academic peers at UCLA and UC Berkeley, when I study poverty, racism, immigration and related issues impacting racial minorities in this country, I do so as an insider and outsider. As an insider, I have direct experience about these issues and, as an outsider, I am too far removed from the wretched conditions that continue to plague millions of Latinos, African Americans, Native Americans and other historically disenfranchised groups in this country.

In short, to me, the aforementioned issues are both personal and professional, where I conduct myself in an ethnical and objective manner.

In addition to your career as a professor, you are also a writer. What moved you to enter this arena or was this something that you always wanted to do in life?

Despite attending mostly inner-city public schools, starting from an early age, I excelled in mathematics and the sciences, particularly physics. I didn’t pay too much attention to reading and writing. In fact, I blame my K – 12schooling at the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) for being average in these subject areas prior to enrolling at UCLA. It didn’t help, for example, that I only read one book, Steinbeck’s “The Pearl,” and only wrote one, two-page paper throughout my LAUSD education.

Consequently, like many teens from the inner-city, I had a lot of catching up to do at UCLA to compete in university-level reading and writing against most of my peers who attended excellent K – 12 schools, especially expensive private schools, like Harvard-Westlake School and Brentwood School. To compensate for not being prepared in these key areas throughout my university studies, I relied on the strong Mexican work ethic, which I learned from my late mother. In brief, I essentially taught myself how to read and write at a very high level during my undergraduate years and beyond. To do so, I read many books on writing by great authors in several genres. This included William Strunk Jr., E. B. White, John R. Trimble, Diana Hacker, Natalie Goldberg, Carlos Fuentes, Jorge Luis Borges, Mario Vargas Llosa, Richard Rodriguez, Gabriel Garcia Marquez and many more.

Before I knew it, I shed my identity as a “young math wiz” and eventually transformed into a scholar/writer. Since I feel morally compelled to educate the world on the plight of los de abajo/those on the bottom, writing became an important avenue for me to engage in this life-long endeavor. I do not just write for the sake of advancing my academic career, I also do so as part of my vocation to write the stories and histories, like the great Howard Zinn, about those who have been forgotten in the history books found in our K – 12 schools and universities. For instance, I aim to tell or write the stories of the important contributions to our society by domestic workers, like my late mother, and farm workers, like my late father.

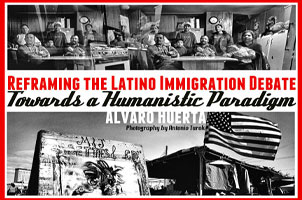

Yourecently published a book on immigration,Reframing the Latino Immigration Debate: Towards a Humanistic Approach. Why this topic and this book?

In this book, I challenge the lies, contradictions and hypocrisies articulated by American leaders and the public about honest, hard-working immigrants and the working-class in this country. I am highly motivated to expose those in power in particular who take advantage of individuals or groups who lack the power or resources to defend themselves.

While finishing my dissertation at UC Berkeley, I started to take breaks from my thesis to counter the arguments articulated by both Republicans and Democrats against undocumented immigrants. Since I didn’t really see any other scholar or national Latino leader defend undocumented immigrants without first apologizing for them or qualifying their remarks, I decided to write this book as a series of social commentaries in defense of immigrants as human beings. In this book, for instance, I argue for amnesty and reject all efforts to militarize our borders and punish workers for feeding America’s addiction to low-wage and exploitable labor.

In your book, you cover several controversial topics, such as Immigration amnesty, the Dream Act, and Jan Brewer, as well as many others. Was this done to inform, shock, or to instigatedialogueto best solve this problem that permeates our country, today?

As a scholar, I believe in free speech. Also, since I have no political aspirations or own stock in any corporation with ties to Homeland Security or belong to either major political party, I have no personal or professional obligations to parrot what others want me to say or write. Also, as a son of poor Mexican immigrants with family members who arrived in this country with and without legal status, I can empathize with the plight of Latino immigrants. While I empathize, however, I am still objective and critical about the entire migration enterprise in this country—including those Mexican nationals who exploit their own people by kidnapping and exhorting thousands of dollars from them throughout their treacherous, migration journey.

Thus, I don’t shy away from the controversial issues, such as advocating for amnesty for the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants in this country or directly challenging President Barack Obama’s inhumane deportation record of over two million individuals, as of this interview.

In general, my task in this book remains a basic one: to reframe the national discourse away from border enforcement measures. Instead, I argue that we should treat all honest, hard-working immigrants with dignity and respect, regardless of their legal status.

Do you think that the immigration debate is being handled adequately on the political arena? Please elaborate.

I strongly believe that the ongoing immigration debate and stalled bills in Congress, if passed, will only harm the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants. All of the proposals from both Democrats and Republicans start and end with draconian measures, such as border enforcement, employment verification, fines, penalties and so on. This makes no sense to me on an intellectual level, especially since American employers and consumers (that’s all of us) highly depend on this vulnerable workforce to meet our basic needs of food, shelter, transportation, etc…

As you wrote your book, how much research did you conduct and how long did this take?

A lot of research and reflection went into my first book. Given that I wrote it over several years, it was manageable. In addition, I regularly read several newspapers and watch cable news channels, so I have the advantage of being up-to-date on current events in order to write timely and topical issues related to immigrants and the working poor. As part of my research and writing process, I aim to contextualize the immigration debate in historical terms. For example, when writing about Obama’s fixation with deportations, I conducted research on “Operation Wetback” of the 20th Century and how the U.S. government has historically mistreated Latinos, including immigrants, residents and citizens.

What was the most difficult part of writing your book and what was the most rewarding? Why?

This most difficult part of writing this book was to write in a language that’s accessible to a broad audience. In the tradition of Howard Zinn’s “A People’s History Of The United States,” I wrotea book for many audiences, including students at different levels (e.g., high school, university), teachers, scholars and elected officials, etc. The most rewarding outcome of my first book was to demonstrate to the world that a “former-kid-from-the-projects” can also write a book with endorsements from world-class scholars. This includes a preface by the great historian, Dr. Juan Gómez-Quiñones,and photographs by the critically-acclaimed photographer, Antonio Turok.

If you had to compare publishing and marketing, which do you find more challenging or frustrating? Any do’s and don’ts for our audience?

In this current environment, both publishing and marketing represent major challenges for the vast majority of writers. I am neither the first nor the last scholar to claim that publishing a book for a traditional press (and marketing it) represents a herculean task. For instance, once I had enough essays to publish, I sent out the manuscript to many publishers, particularly academic presses. While rejected by a couple of presses, I operated under a basic premise: all I need is one. This took some time. I also had to do some tweaking. When my current press first considered my book manuscript, I thought to myself, “How can I make it better?” It dawned on me to recruit a well-known photographer, like Turok, to make the book more appealing and marketable. It worked!

In terms of marketing, unless you’re a best-seller author with a major publisher with huge pockets, you’re on your own. While this represents a challenge for most writers, given the current technologies of publishing and role of social media, it’s possible to sell books by taking advantage of social media outlets, in addition to methods, like book talks and word-of-mouth. Also, since I’m an academic, I also have networks within the academy, where my book is found at numerous university libraries and assigned to classes at the university level.

In terms of do’s and don’ts, I only have to say that anyone who aspires to write or become a writer must first believe in herself or himself, in order to get published. Since writers in general will receive many rejections over their careers, it’s easy for an aspiring writer to give up. Rejections don’t stop me. I don’t take them as reflections of my self-work or self-esteem. In other words, I don’t need anyone to validate my self-worth or who I am. This is something that I advocate for others to embrace. At the end of the day, if an aspiring writer doesn’t get published by a traditional press, then she or he can self-publish! Again, the aspiring writer needs to believe in herself or himself.

Finally, aspiring writers forget the three P’s: practice, practice and practice!

In spite of all the obstacles of poverty you experienced, you have achieved great success in your academic and writing careers? Whom do you mostly give credit to? Parents, friends, teachers, yourself, or a combination?

This is a common question that I get from people that I just meet. This question also applies to my brother, Salomon Huerta, who happens to be the most successful Chicano/Latino painter in the U.S. While I have a long answer for this question, for the sake of space limitations, I would say that it’s a combination of benefitting from existing programs to pure luck to “natural” skills to relying on key individuals.

For instance, attending Upward Bound at Oxy had a major impact in my desire and preparation to pursue higher education. In addition, being a thin kid/teen from the projects helped, since I could never join the local gang, even if I wanted to. Like I jokingly say, “I was not gang material” or “My gang application was rejected.” Moreover, I attribute my math skills as a kid/teen as an important reason why I attended UCLA, as a freshman. Like an elite football player or boxer who escapes his or her bleak environment due to their athletic skills, my math skills allowed me to escape the projects.

Lastly, apart from my late parents and a couple of teachers, my wife had a lot do with my success. I’ve had the fortune to marry a wonderful and wise Chicana, Antonia, who has constantly pushed me to excel. Without her ongoing support, I don’t think that I would have reached the majority of my professional goals, particularly after enrolling at UCLA, where we met and have been together ever since.

Who is your toughest critic?

I am always my toughest critic. While I sometimes bump into someone who tries to undermine me or my efforts, I usually disregard unsolicited criticism, particular when no constructive input or feedback is offered. While all writers and scholars should be open to criticism, which comes with the territory, I am against all mean-spirited or destructive criticism. That said, I am a perfectionist, which is great when things work out, like my recently published book, yet torturous when things take a little longer than originally anticipated to complete.

Do you have any technical writing advice for our readers?

If you someone wants to write and become a writer, first, she or he needs to learn and master the craft of writing. I believe in both traditional forms of learning the craft of writing, which includes university training and independent studying, as I’ve noted above in the form of self-studying. At the end of the day, however, there’s no getting around it. If you someone wants to write well, she or he needs to read a lot, especially the great writers of any given genre and write daily! To start the daily writing practice, be it for 15 minutes or one hour, the aspiring writer should read Natalie Goldberg’s classic book, “Writing Down the Bones: Freeing the Writer Within,” along with her other fine books.

If that fails, I’ll just repeat what I tell my students at UCLA, UC Berkeley and beyond: “If a former kid from the projects with non-literate parents can do it, so can you!”

At the end of the day, what do you hope your book(s) will accomplish? What do you want your readers to take away, after having read your writings?

I want my books to transform the world for the better, while writing beautiful prose, like Franz Fanon, Ricardo Flores Magón and Isabel Allende.

I want my readers to see the world through an alternative viewpoint. A viewpoint that’s intolerant for hunger, poverty and violence, especially in a country with so much wealth and power. A viewpoint that argues for theory and action on behalf of los de abajo/those on the bottom.

Do you have any upcoming projects in the near future that you would like to share with our audience?

Yes, I’m currently working on my second book for a major university press. Focused mainly for the academic market, it’s based on Mexican immigrants and their social networks in Los Angeles’ informal economy.

Contact: https://sites.google.com/site/alvarohuertasite/